Do you remember where you were on February 1, 2003?

Let me remind you.

As you were leading your peaceful terrestrial life, the space shuttle Columbia was disintegrating over the skies north of Dallas, Texas. All seven astronauts perished.

The cause of the accident happened two weeks earlier. Eighty-two seconds into Columbia’s liftoff, a piece of foam insulation, about the size and weight of an empty brief case, tore from the external fuel tank and slammed into the leading edge of the left wing at approximately 600 miles per hour.

The collision shattered heat tiles critical to protecting the shuttles flight surfaces and controls from the incinerating 3,000 degrees the vulnerable space craft would experience upon re-entry.

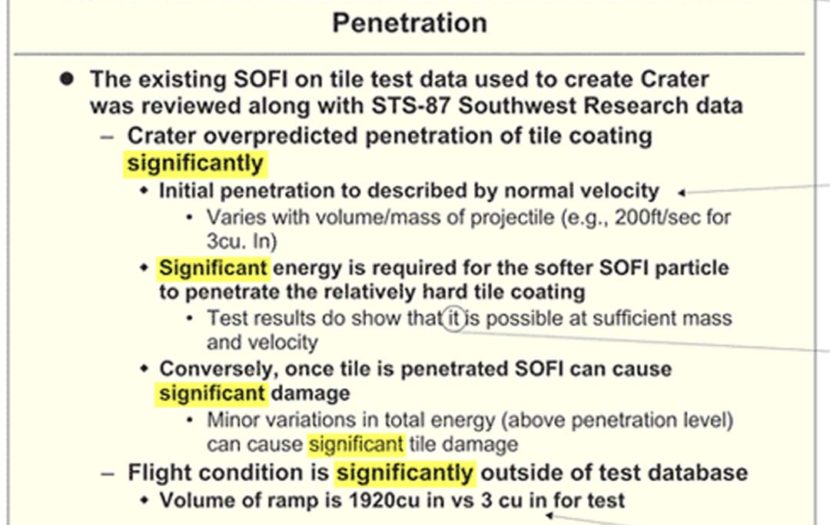

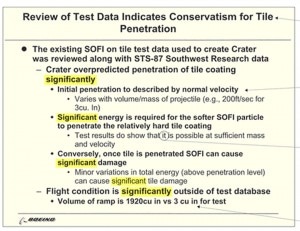

A powepoint slide from Boeing engineers who were assessing the damage while the Challenger astronauts were orbiting earth.

Although the seemingly innocuous piece of foam was blamed for the demise of Columbia and its astronauts, the ultimate culprit was uncovered in the space agency’s use of powerpoint.

Several studies, including a now famous one by Edward Tufte, blamed the over-reliance of powerpoint by shuttle engineers, which innately obfuscates information by virtue of its low-resolution presentation characteristics. Studies like Tufte’s also suggest that the lack of clarity in powerpoint presentations was a leading factor in the Challenger accident.

Ever since we put a man on the moon, I’ve been enamored with America’s space exploits. We obviously need the brilliant scientists and engineers to make it possible. But of equal importance are the storytellers: the communication professionals that can translate the data into meaningful narrative.

Edward Tufte, the man the New York times called the “Leonardo Da Vinci of Data” tours the country with an exceptional workshop that I took called Presenting Data & Information. Wired magazine said,

“One visionary day….the insights of this class lead to new levels of understanding both for creators and viewers of visual displays.”

My point in all of this is that people are not moved to action – even in life or death circumstances – by facts and figures. They need to be invited into a compelling story that focuses on the event that the data is predicting will happen, or has recorded as the outcome. The data in and of itself is not the story. When data is communicated in context, with metaphor through story, then meaning is created and people become inspired and moved to action.

Are you turning your data into drama?