Leadership Storytelling Similarities Between the Righteous and Riotous With Randy Olson

What do presidents Abraham Lincoln and Donald Trump have in common?

You might say, “Not much.”

But according to my guest today, they share a rare superpower: narrative intuition—the innate ability to communicate with compelling structure that moves audiences to action.

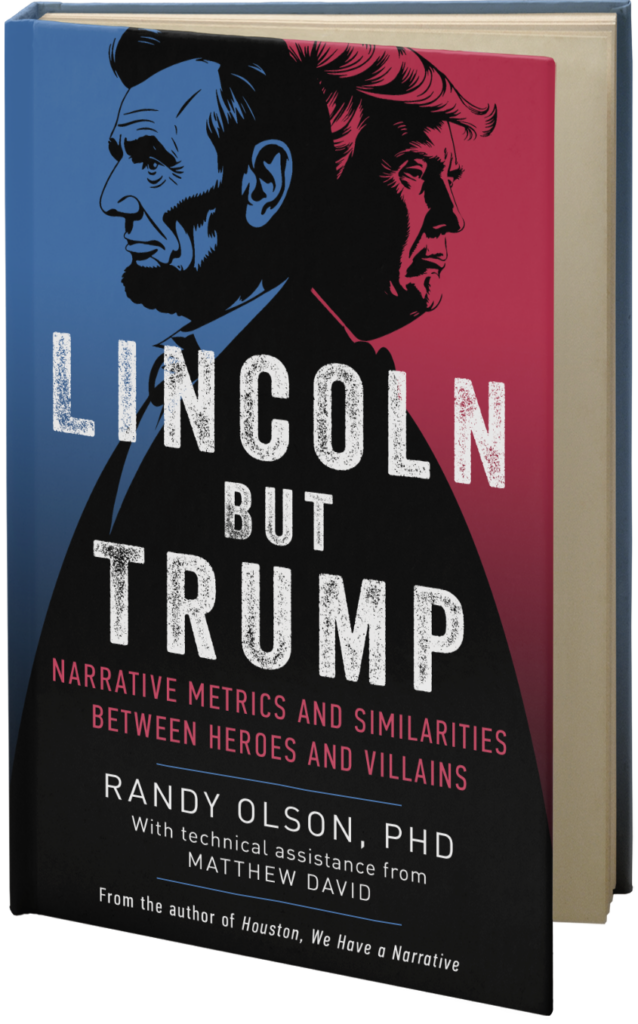

Dr. Randy Olson is an evolutionary biologist turned filmmaker and author of the eye-opening new book Lincoln BUT Trump: Narrative Metrics and Similarities Between Heroes and Villains.

In it, Randy reveals how two simple metrics—AND Frequency and the Narrative Index—can measure the strength of your messaging and diagnose the difference between boring information dumps and persuasive storytelling.

You’ll discover why leaders who win hearts and minds, whether you like them or not, don’t necessarily have better ideas—just better narrative form.

So if you want to elevate your communication, cut through the noise, and lead with clarity, you’re in the right place.

Let’s explore the science—and the story—behind impactful narratives.

He has written and directed a number of short films and feature documentaries, which have premiered at film festivals such as Tribeca Film Festival and Telluride Film Festival.

Most of his films draw on his science background, involve humor, and address major science issues such as the decline of the world’s oceans, the controversy around the teaching of evolution versus intelligent design, and the attacks on global warming science.

Olson has also written twelve books that teach scientists and academics how to simplify complex communications using story structure, especially the ABT (And, But, Therefore) narrative framework.

What’s In It For You:

Learn how to grade the power of your communications using the And Frequency and Narrative Index metrics.

Learn how to grade the power of your communications using the And Frequency and Narrative Index metrics.- Why Lincoln’s communication style was more effective than Douglas’s due to narrative structure.

- How Trump’s communication style is transactional rather than narrative-driven.

- The media environment selects for certain types of communication.

- The words ‘and’ and ‘but’ are powerful tools in language.

Chapters:

- 00:00 Introduction and the Power of Storytelling Frameworks

- 06:04 The Role of Media in Shaping Narratives

- 09:00 Analyzing Lincoln and Trump: Communication Styles

- 11:52 The Evolution of Communication and Its Impact

- 15:08 The Metrics of Narrative: Understanding ABT in Practice

- 17:56 The Influence of Media on Political Communication

- 20:58 Conclusion: The Future of Storytelling in a Media-Driven World

- 29:04 The Power of Language: ‘And’ and ‘But’

- 30:01 Quantifying Language: The Narrative Index

- 31:00 Historical Context: Lincoln vs. Trump

- 32:44 The Importance of Conflict in Communication

- 35:29 Media Influence on Political Communication

- 38:20 Engaging the Limbic Brain: The Role of Storytelling

- 39:46 The Structure of Effective Communication

- 41:55 The Evolution of Storytelling Techniques

- 43:51 Real-World Applications of the ABT Framework

- 46:47 Metrics for Effective Communication

- 49:48 The Role of Humor in Communication

- 51:42 Forensic Analysis of Communication

- 53:35 Promoting the ABT Framework

Links:

- Lincoln BUT Trump: Narrative Metrics and Similarities Between Heroes and Villains

- Randy Olson on Substack

- ABTnarrative.com

- Randy on X

- The StoryCycle Genie™

Popular Related Episodes You’ll Love:

- Learn From My 10-Year Journey With the ABTs of Storytelling with Park Howell

- How to Tell Your Startup Lifecycle Story to Sell Investors & Customers on Your Brand with Gregory Shepard

- How to Persuade a Judge and Jury Using the ABT with Doug Passon

Your Storytelling Resources:

Connect with me:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/parkhowell/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/BusinessOfStory

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC0ssjBuBiQjG9PHRgq4Fu6A

Twitter: https://twitter.com/ParkHowell

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/parkhowell/

Website: https://businessofstory.com/abt/

Transcript of Show:

In this conversation, Park Howell and Randy Olson explore the intricacies of storytelling, focusing on the ABT (And, But, Therefore) framework as a foundational element of effective communication.

They discuss the evolution of narrative techniques, the impact of media on political communication, and analyze the contrasting styles of Abraham Lincoln and Donald Trump.

The discussion emphasizes the importance of understanding narrative structure in a media-driven world and the necessity of iteration in mastering storytelling techniques. They explore the profound impact of language, particularly the words ‘and’ and ‘but’, on communication.

Olson introduces the concept of the Narrative Index, which quantifies the effectiveness of communication by analyzing the use of these words.

Through historical examples, particularly comparing Lincoln and Trump, he illustrates how effective storytelling and conflict can engage audiences.

The discussion also touches on the importance of media in shaping political communication and the necessity of structuring narratives to capture attention. Olson emphasizes the application of the ABT (And, But, Therefore) framework in various fields, including business and academia, to enhance communication effectiveness.

Park: What do Lincoln and Trump have in common? You might say not much, but according to my guests, they share a rare superpower, narrative, intuition, the innate ability to communicate with compelling structure that moves audiences to action. Whether you like it. Or not. Hi, I’m Park Howell and welcome to the Business of Story, my pal, Dr.

Randy Olson, evolutionary biologist. Turn filmmaker is the author of the Eye-opening New book Lincoln, but Trump narrative metrics and similarities between Heroes and Villains. In it, Randy reveals two simple metrics. And frequency and the narrative index and how they can measure the strength of your messaging and diagnose the difference between boring information dumps and persuasive storytelling.

You’ll discover why leaders who win the hearts and minds of people. Don’t necessarily have better ideas, just better narrative form. So if you want to elevate your communication, cut through the noise and lead with clarity, you are in the right place.

Park: Hey, Randy, welcome back to the show

Randy: Once again.

Park: Is this your sixth, their seventh appearance here on the business of story? I hate it’s,

Randy: It’s more than that. It’s, it’s around eighth or ninth. They’re, they’re a couple small. Parents as well.

Park: Well, you’ve certainly earned it. You taught me about the and, but therefore in your second book called Connection, and I learned about that back in 2013 and it kind of blew me away.

Like the hero’s journey blew me away when I first learned about that. But the hero’s journey being 12, 16 steps, whatever. The a BT being these three words that make all the impacts that it, I, it’s something I wish I had learned in the third grade.

Randy: I get that a lot. Um, you know, I gave a talk once at Princeton and at the end of the talk, a woman I.

Raised your hand and said, I wish I’d known this six years ago. Um, at the start of my dissertation work, and while you were speaking, I did the a BT for all each of the chapters of my dissertation. And I’m just shaking my head like, this would’ve been so valuable over the years.

Park: Well, you’ve taught it forever in the science and the academic world, and I’ve tried to translate it over to the business world and we use the exact same framework.

I use it just a little bit differently, I think in the business world, but I was delighted to see a couple weeks ago, uh, Eric. Partaker. I don’t know who Eric is. He has quite a large following and I think he’s a business consultant guru out in London somewhere. And he came up with a graphic, he said six storytelling frameworks.

Every CEO needs to know, uh, Simon Sinek’s Golden Circle, which I’m not really sure that’s an actual framework, but I’m glad to see it in there ’cause I like it. Mintos. Pyramid Principle, which I’ve never heard of before. Interesting. Oh, actually

Randy: That’s very wide. I think the people at McKinsey or something like that use it.

I, okay. The people at, uh, at Deloitte, when I did some work with them, they, they brought that up.

Park: They did it, yeah. Yeah. And then they have the Pixar pitch, which everybody tries to do, but doesn’t do it very well out there in the world. But I like to see that in there, the StoryBrand framework, which really, to me isn’t exactly storytelling.

StoryBrand to me is like. Branding Botox, it’s very good to create a, a landing page that can convert, but it’s not really true storytelling in the sense of the world, but I like seeing it there. Um, the what, so what now? What? And then you occupy the bottom right hand corner, Randy Olson’s, a BT, and, but therefore, framework.

Randy: Yeah, that’s kind of nice little validation. Um, I think we’re, this past year we’ve been hitting a, a tipping point with it. And when you look at that diagram there, that’s nice. The other five models, whatever they are, they’re kinda like different brands of automobiles, different cars. Which are great, but inside of each one of ’em is the engine, which is the A BT.

And so the A BT, this tripartite structure kind of drives all of those things. When you look at all of ’em, they’ve all got kind of three part structure to them and they’ve just done different variations on that. But at the end of the day, and deep inside the A BT is just capturing the three central forces of narrative, which are agreement, contradiction, and consequence.

And when you realize those are the three forces, and you look at the first force agreement, the most commonly used word of agreement by a long ways is the word. And so that’s how we get the first word of the, the a BT. The second word, uh, the most commonly used word of contradiction is, but, and there are all these websites that list a hundred most commonly used words in the English language you always see.

And in the top three. Then Bud is usually somewhere between 15 and 25 and there are, there are a bunch of other words of contradiction. However, yet despite things like that, none of them show up in the top 100. So that’s a lot of how we get the A BT to begin with is that those first two words embody I.

These two fundamental forces. The third one, consequence we use the word therefore probably so is more common, but therefore is a more powerful word. But that’s the origin of the A BT and that that just shows you how primal it is basically. It really, all those other things are kind of downstream from it.

Park: Yeah. Well we call it the DNA of storytelling because of what you said. It is the engine. Everything is built and hung on the setup, problem, resolution, dynamic of the ambu, therefore.

Randy: And by we you mean me, you mean Park Howell, the guy who early on looked at it and said to me, you know what, this sure seems to me like it’s the DNA of story.

And then we have clung onto that and it’s in a bunch of the books that I’ve written, all that sort of stuff. ’cause you’re, you, you. You know what? You, you get the award for one of the earliest adopters, one of the, the people that just in an instant saw it and got it. And they’re the vast majority of people, like, I don’t know about this thing.

We are a media driven society and people are driven so much by media, media exposure. And that Pixar model, I guarantee is driven mostly by brand name. Oh, Pixar. Yeah. I gotta learn that one. Yeah. They make nice movies, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they’ve got the best tool to teach you how to use narrative.

Create narrative structure. So that’s the way things work. We, we run into that with some of the science organizations that we work with. There are some of them that ha, I won’t mention their names, but there are two or three that have very prominent brand names. And people from those organizations have a tendency to think they’re brilliant communicators.

’cause they know at a dinner party, all they have to do is say the brand name of the organization they work with and everybody stops dead. Oh my God. You work with them and that doesn’t mean you’re a good communicator. It means that you’ve got the power of some other people that created this brand that gets attention.

But that happens all the time.

Park: Yeah. And there’s a big difference between sitting in a movie theater and watching a Pixar movie and trying to then use the Pixar storytelling technique to persuade a bunch of investors or scientists or colleagues to do something

Randy: You want them to do. Yeah, yeah, exactly.

And, and this stuff is so endlessly challenging. That anything you’ve got along the lines of simplicity, working your, your favor is, is really powerful. And that’s what we work with so many people that are just so lost in so much information and they. They know they do a lot of good work, but they can’t even, you know, as you prob as I think, you know, you’ve worked a lot with this on this, um, the, the starting point for everything is what’s the problem?

You know, what’s the problem at the core of your narrative? And we work with people that are running the million multimillion dollar projects, and you ask them what’s the, what’s the one main problem at the center of what you’re doing? All of a sudden you just get this deluge of, well, we work on this, we’re there, we’re interested in this.

We’re thinking about this. I know, but can you tell us what’s the main one thing that’s the challenge in a world of too much information?

Park: Well, and we’re gonna be talking about today, your new book, Lincoln, but. Trump narrative metrics and similarities between heroes and villains, and you’ve already received a bit of heat from some of your world about why are you glorifying Trump in this.

But it’s not about glorifying Trump, it’s about, as you’ll talk about here, a little bit of. Evolution and where we are selecting is homo sapiens for simpler, more straightforward dialogue. Narrative as we are being overrun with content.

Randy: That’s where we are today. And you’re right, uh, one of my old professor buddies who was always the most.

Vicious critic of every manuscript anybody ever gave him. Uh, he is a great, great guy. And so I figured, yeah, let’s, let’s start off with the acid test here. And I sent him the manuscript a couple weeks ago and he ripped into it, and that was what he started with. You know, how dare you even mention the name of this guy, Trump, yada, yada, yada.

It kind of helped me shape the little warning that you see on the very first page of the book, which says, this book is not any sort of endorsement of Donald Trump nor any of his content. It’s just an analytical look at, um, his style of communication and compared to others. And that’s exactly what it’s about.

And the, let’s start with the title Lincoln, but Trump those three words, uh, that tells a whole big story right there, which is, you know, it’s great to sit there and admire Lincoln and to. Read all of Doris Kern’s Goodwin’s books about how amazing Lincoln was with his team of rivals and this, that and the other thing.

And just, you know, hundreds to thousands of books probably written over the ages about the brilliant speeches he gave and all that sort of stuff, and lots to admire there. But when you’re done reading all that stuff, you really ought to pull your head out and look at today’s world and the fact that we have a president right now that has dominated this country for the past 10 years.

He’s dominated because he has such deep narrative intuition, and one of the starting points is to make sure you realize the difference between Reagan and Trump. Reagan was a storyteller. Trump is not a storyteller in any way, shape or form. That’s not what this, if you think that he’s a storyteller, you don’t even begin to understand what narrative structure is about.

Trump has deep narrative intuition. What that means is. He walks into a room and he’s not gonna tell any great stories. He just wants to get right to the deal. What’s our problem here? You know, what’s the setup? What, what is it we’re working with first off? And then what is the problem that’s keeping us from having a deal?

And then therefore, what’s our solution? And that’s it. You know, they keep talking about how he’s. That, that’s, he just wants to make these deals and the, I don’t know what his interests are in the human side of, of humans. I don’t think anybody quite understands. I think

Park: It’s self-interest. There’s no interest in the human side.

It’s Donald Trump’s interest.

Randy: Yeah, exactly. Transactional is what they keep labeling as. He’s very transactional. That’s it. He’s not a storyteller. He is transactional, but

Park: he is very

Randy: Effective. He’s got the whole world shaking. He, he’s been selected for in today’s realm, and that’s what you’re pointing at.

And that’s exactly the context that I put this all together. And so, yeah, one of the unique things with this book is that long, long ago I was a, a biologist, an evolutionary biologist. I did a PhD in evolutionary biology at Harvard University, and I got to spend time around the greatest. Minds in the science of evolution ever.

Basically, specifically Stephen J. Gould, more than anybody else who wrote a lot of books and tremendous popularizer of, of evolution science. And the thing that’s a shame is that there, he, he died in 2002. There’s nobody comes close to him for being able to communicate and popularize. He was a great, he had great narrative intuition and he wrote these essays explaining that these are the evolutionary principles.

Evolution is the science of change. That’s our biggest challenge is to try and figure out how are things, why are things changing? You know, why can’t we just lock everything in and have it never change? You can’t do that. Everything’s always changing and there are these forces that drive the change and result in patterns over time, and the patterns largely result from selection.

That’s what Charles Darwin figured out. Gould was great at explaining it to everybody, and that’s the way to look at today’s world. Is that we’ve created this media environment. The, the media landscape I talk about in the book and it selects for different types and things and, and voices, and it’s selected for our current president.

But here’s one of the most interesting things, for starters, maybe this’ll light some fires in some of your folks to wanna read the book. ’cause by the way, it’s incredibly short book. It’s ridiculously short, it’s 12,000 words. Typical novel is about, you know, upwards of a hundred thousand words. And so this book, you get to the end of the the 12,000 words, which is the equivalent about one chapter in a novel, and then there’s Postscript that says, okay, you’re not done.

You’ve read chapter one. Go back and read this thing eight times, and once you’re done reading it eight times, you’ll have read the equivalent of a novel, and that’s how you will learn this. A BT tool is through iteration. If you don’t. Read it and work with it repeatedly. You don’t pick this stuff up. It it, it suddenly set me to thinking, you know, how does anybody think they ever learned much of anything from reading a, a book once that’s great for an entertainment experience, but to really learn how to do something, it’s in the iteration.

And so that’s what you need to do over and over again. And one of the most fun things about the book, as short as it is, there’s just two main chapters. Chapter three is about the whole story of the World Bank. I’ve been working with them for three years, but

Park: There’s no way. You just threw a contradiction in there.

There’s just two main chapters. Chapter 3 0

Randy: 2. No, I said two main, main chapters.

Park: Oh, okay.

Randy: Yeah, yeah, yeah. No, there, there’s, I think there’s seven chapters. But Mo, most of ’em are real short. It’s just, I gotcha. Yeah. Chapters three and four. Okay, let, let’s, that’s because I’ve

Park: Read it, but I just heard you say that.

I thought my listeners are gonna go, what?

Randy: Yeah, no, now you missed the word main. So there’s two main chapters. Exactly. And you know that you read it. So there’s two really thick chapters. There’s the chapter on the World Bank, which is the whole story that took place at the Royal Bank. Then there’s the chapter about the Lincoln Douglas debates.

Those two chapters give rise to the two metrics that are at the core of the whole book. So the, the chapter on the World bank gives rise, rise to the hand frequency. That’s the first metric that we introduced in the book. But the chapter four is about the Lincoln Douglas debates of 1858. And the more I dug into that, the more fascinated I became.

So here’s the deal. Let’s see if I can. Kind of presented in this in fairly concise terms. 1858 was a pretty pivotal year in terms of the change of technology, of communication technology in this country. At the beginning of the year, people were still mostly just delivering mail by pony, express by horse, things like that.

But during that year was the coming together of the completion of a lot of the railroad lines to the major cities, number one. Number two, the completion of a lot of telegraph lines. For electronic communication, like that, instant communication. And number three, very important, relevant was the advent of sonography, making it possible to transcribe an entire speech on the spot as opposed to just, you know, reporters going off and trying to remember what they heard.

In the summer of 1858, they ended up having seven debates, a series of seven debates, started in August and went through October. State of Illinois, and at the beginning of that year, Abraham Lincoln had been a congressman like a decade earlier, but that was about it. He just served one term, was back there, and he was just kind of a lawyer hanging out, but with political interests.

And Stephen Douglas was coming up for reelection to the Senate and so Lincoln started showing up. At Douglas’ Debates almost heckling him and just asking tough questions. And everybody began to see this kind of rivalry going on between the two of them. And eventually the forces came together to stage these seven debates as Lincoln announced that he was gonna be running against Douglas.

So they were in, I think they’re like nine major districts of, um, uh, in, within the state of Illinois. And so these are the main seven ones outside of Chicago. And. The debates were enormous. They were three hours long, and the first guy got to go for an hour, and then the other guy got to go for an hour and a half.

Then the other guy got a rebuttal, finish it up, and they were all transcribed. And this turned out to be the first media event in the history of this country. It was the first time. The, and, and think about what that means, a media event, because you know, I get into eventually Marshall McClean later in the book, but Marshall McClean was kind of the, the great media scholar, and what he defined media as is the extensions of man.

That’s the subtitle, his book. And so when you’re there in person with people, that’s not media. You can say something and you’re there to explain and defend it, but as soon as your words start getting put into something else, namely in print. Or on the radio or on television, that’s media. You’re no longer there to control it.

And so Marshall McClean’s great, uh, catchphrase was the medium, is the message. You know, once that happens, that the medium has got control of your message, you’re not there to, to manage it anymore. And so what happened with those seven debates, this is what’s so fascinating, was that there were two audiences.

There was the live audience there at each of the seven debates. They heard the performances and. They all mostly leaned towards Stephen Douglas. They thought he kind of won these debates. He was a foot shorter almost than Lincoln, and he was full of energy. Talked to Milam Minute. One of the reporters described him as a Gatling gun of words, just spewing out all this stuff.

Lincoln was, was much slower, more thoughtful in his delivery, but also there was a difference in the structure of what they were delivering for information. In the language of the A BT. Stephen Douglas was an and, and, and candidate. You know, he was just going on and on with this and this and this and this and this, and there was all this energy.

’cause he talked so fast. Lincoln was slower, more thoughtful and constructing a BT material. And we can see that now. This is what I presented the book is when you look at the transcripts. You can see the difference that there it is that Douglas’ stuff is just end and, and and, and there’s hardly any buts in what Douglass was saying.

And there’s the buts in Lincoln’s material. Yeah. Over and over structuring this ABT material. So the result was you had a live audience that thought that the wild man running back and forth on stage was the winner. He was so exciting and so InVigor and yada, yada, yada. And this other guy is kind of slow and old, but then you had the remote audience with the transcripts.

Through sonography being transcribed, got into the big cities, and eventually two or three days later appearing in the major newspapers all around the country and that audience. Was consuming it differently. They were reading it on the written page and it was far more engaging ’cause of the ABT structure, what Lincoln did than this, blah, blah, blah, blah, from Douglas.

The net result was by the end of the year, Lincoln had emerged as a major character, and those debates were the transitional thing for him that took him from zero to Hero by the end of 1858 at this media event. So all that I find incredibly fascinating and then you parallel that. What’s happened in the past decade here, which was,

Park: okay, let’s hold on that for just a second.

Yeah, yeah. Because if people go well, is that just coincidental that he’s got this ABT structure? Obviously he didn’t know the ABT back then, but he was a, just a very good intuitive. Storyteller, and you can see that in Gettysburg. Yes. Went and looked at Gettysburg. It’s a two minute speech. It’s two embedded ABTs.

And if you have any doubt whether he had this great narrative intuition, just go and look at that simple little speech and you’re gonna see it right there. I.

Randy: Who was the first guy to ever spot the ABT structure in the Gettysburg of Draft? I, I’m

Park: Trying to think who… The same guy that came up with ABT as the DNA of storytelling.

Randy: Need to know. That in the beginning I started stumbling around with this ABT thing ’cause I was the first one to pull it together into this template of, and, but therefore, and then Park is the guy that called me up one day and said, did you ever look at the Gettysburg address?

I said, no. Was that, that’s, that’s the depth of my historical intellect and this is gonna be one of the problems. You know, that all the real historians are gonna hate the idea of me trying to even set foot into the. The whole subject of Lincoln and Douglas, but I don’t care. You know, it’s, but it’s

Park: right there.

It’s in print. Right. And you’ve even run the analytics on it. We’re gonna talk about that here in a minute too. It’s clear. Yes. So it’s over there. Right? Go ahead And now let’s jump forward to this last decade.

Randy: O Okay. So then, yeah, and this again gets back to the title, which is that, so Lincoln was selected by this changing communications environment.

And that probably wouldn’t have happened a few years earlier. There wouldn’t have been that ability to get this out into the newspapers all around the country, for everybody to hear his voice that way. It would’ve just been the people that were there writing in newspapers. Well, you know, I thought the crazy man was the guy that won.

So he benefited from a change in the environment. It’s selected for a different candidate there. And now we jump to present time and the emergence of Donald Trump, who. Was pre adapted for today’s media driven landscape. And this is my argument there, and I will continue to argue this until some of these people in the political world really hear this.

Because we are a media driven society. We’re not driven by politics. We’re not driven by religion. We’re not driven by values. We’re driven by media more than anything else. We know this. The media’s incredibly powerful, and now it’s social media as well, driving all these sorts of things. And so Donald Trump was, I mean, I think he was pre adapted to the media world to begin with, which is why he stepped into the Apprentice and things like that so easily.

But that just furthered his narrative intuition and his communication skills to the point where. He has this very, the, the word that that comes out in a lot of linguistic studies, uh, the term parais. Do you know that term arc? No, I, I read it in your book. Yeah, there you go. And you read it in the book, because I didn’t know that term as well.

Exactly. I read it in this study of the World Bank from Stanford Literary Lab. And it, I think it’s a very practical term that people need to start thinking about parais. What it refers to basically is. Communicating with sent sentence structure that removes is very choppy and removes a lot of the connector words.

And the day was, was bright and the sky was sunny. Birds walked, you know, on the, the side. Are you talking

Park: Hemingway here? I mean, he wrote that style? Um,

Randy: no. Well, maybe a little bit, but it’s, it’s just a, a, a style, a literary style. Exactly. Mm-hmm. Which is short and choppy. And then the technical term for it is para taxes.

That it, it’s, it’s very similar to editing in a film. You know, it’s, it’s ellipsis, it’s leaving out chunks that the brain can go ahead and fill in the details and you can run us through a lot of story points really quickly like that. And it’s very stimulatory. And look at how Trump communicates. I mean, everybody makes fun of this Saturday Night Live, you know, is just constantly parroting his mode of speaking and yet.

I would argue it was kind of pre adapted to look. What also happened, just as he decided to run for president, was the emergence of Twitter and Twitter sprung to life really around 2013 and 14. I wrote about it in my 2015 book, Houston. Uh, we have a narrative and there’s an appendix in there in which I made the prediction, which was that Twitter’s, the tweets were too small.

There were only 140 characters, and in that appendix I say you can’t fit a whole ABT into 140 characters. And if you can’t fit the three elements to set up the problem and solution, it’s gonna select mostly just for the problems. It’s not got enough time for setup so you don’t get any context, and he’s got time to stick around for the consequence.

That’s exactly what was happening. It was all, you were getting, all this noise on Twitter was just all, you know, people complaining about this and this is all just problem, problem, problem. They eventually, I, I had predicted either they’re gonna have to increase the size of the tweets or they’re gonna lose their audience.

And sure enough, right after my book was published around 2015, they doubled the size of the tweets and one of the kind of defining moments as a whole. Big debacle they had was Stephen Colbert, where he was taken outta context on Twitter and everybody wanted, uh, comedy Central to fire him as a racist when in fact if you could have fit in the whole context of the joke wasn’t racist at all, it was, uh, yada, yada.

At any rate, that was the landscape, the media landscape into which Donald Trump ran. For president and his style of communication and Twitter and all of those sorts of things. And also interesting to note was that Barack Obama, at the end of his term, his second term, he began to experiment a little bit with Twitter.

And he treated it, you know, as Barack Obama. And with all his dignity would do, he treated it with, with delicacy and sort of respect and not even sure if this was the right thing for a, a president to even use. Next thing you know, you know, president Bull in the China shop comes in and takes over Twitter and uses it as his mouthpiece.

Um, you know, Trump never hesitated to get on there and just blast and, and use it differently than anybody had ever imagined. I. But that again was the changed media landscape that selected for him and his style. And there’s lots of other things that go with it. But the fact is there were lots of other candidates over the years that have spewed all kinds of similar sorts of, of content that he has for messages and things.

He has had this style of communication with deep narrative intuition that has managed to captivate and and unify. A huge audience for him. And so, and you see him manifest in all different aspects, starting with the red hat and the short little slogan. That little slogan comes right out of ABT structure.

So, you know, the bigger form of what his whole candidacy was built around was, uh, we are a great and mighty nation, but we’ve slipped in the world. Therefore it’s time to make America great again. And the logic that. Came out of him then is, I hate to tell you, but it’s very similar to Lincoln in terms of the structure and the way that we can see that is through the, the two me metrics that I developed in this book.

And I’ve been doing this for 10 years. And finally, this is the book that really lays it out, um, in a single sort of story. And the two metrics are, first off, just the frequency of the use of, and. When people use and too much, it bogs everything down. And it’s also reflective of content that’s just not got much of a story to it.

And that is the, the chapter on the World Bank is, it’s titled A Plague of and at the World Bank. And that’s what happened 2015, there was a big study that came out from Stanford literary lab that showed that ever since the founding of the world back in the 1940s, the use of and in their reports has more than doubled.

So in 1946. The frequency of and was roughly two point half percent. Today it’s over 5% and that may seem silly if you don’t know anything about narrative structure, and that’s exactly what the problem was, is that for those who don’t know anything about narrative structure, like, well, Ann’s a dumb word.

It’s like thug. It’s like of, and like n and blah, blah, blah. And there are a whole bunch of those short words that are throwaway words. And they’re at the top of these surveys, the most used words. The only difference is that and has got a, a second life to it, A second function, which is it plays in structure as we were talking about.

It’s the word of agreement with the use all day long. This is how you set up arguments. This is how you set up stories. You begin with all this agreement and this and this and this and this. And then the second word, but is the other structural word, which again. Lots of people think, well, that’s another stupid throwaway word, but who cares about that?

But is probably the most powerful word in the entire English language. Yeah. Um, I’ve mentioned in the book Jerry Graff my good buddy, who is the author of a book called, They Say, I Say, it’s a college textbook, a really short, very effective college textbook for um, use of templates and argumentation.

It’s used in class of rhetoric and comparative literature and has sold over 3 million copies. It is one of the most popular textbooks in all of America today, and I had him in my film Flock Dodos in 2006, and we became good buddies. In fact, I’m probably gonna have him come join our discussion group, by the way, park in a couple weeks.

Um, and you’ve had him on the show before? Yep. Zach.

Park: Yep.

Randy: And Jerry’s great guy. And about three or four years ago, one Sunday, he sent me an email. And said, is it not the case that but is the most powerful word in the entire English language? And I was already having those same thoughts. And he said, I just got through reading this editorial in the New York Times.

And you know the word but is all the way through it. And yes, if you define the most powerful word as. What it does to language and how frequently it is used by every single person in human race, day in and day out, or at least in the English language. Uh, there’s nothing as powerful as, but you know, you’ve got these other words that are descriptor words that may feel powerful, but this is all day long.

Everybody’s guiding conversation, setting it up with Anne, turning it with, but, and once you work with those two words and you really start to soak in the depth of their, uh, their impact on language. Then you start looking around. That’s what happened to me starting 10 years ago. I began counting them and as soon as Trump emerged as a candidate started giving speeches and debate performances, it began to hit me.

It was right when that Houston book was coming out like, oh my God, this guy is constantly saying, but he’s constantly turning the conversation. He’s constantly taking one direction, then immediately, but you know, this, this, and this. And that’s when I began counting and you know, my science training. Taught me long ago.

When you see something interesting out it in the real world in nature, the first thing you wanna do is try and quantify it. You know, better than just telling people, oh, things are really big. How big we want to know a number. How, how long did that last? So I began counting and counting and counting and counting for the last 10 years.

And then five years ago, Matthew David came along and began working with me in the ABT course. He began counting with me and in the beginning he was like, I dunno about this stuff. And then he began to see the pattern. He’s like, wait, this is really interesting. And then starting about three years ago, we began doing this with all the, the course.

Every time we run the course with the organizations, ask them to bring in some of their most prominent documents. And we’d run the two metrics. And the two metrics are just how much you’re using and the, and frequency, the af. Of course AF has other definitions and other people’s use of it. Well, we don’t care.

I think it’s kind of perfect that that’s it. So you got the af, which is very simply what percentage of all your words or the word and And then the other metric is the use of the word, but in relation to and and that’s the but and ratio. And we call that the narrative index of the ni. And you know, I’ve just thousands of documents I’ve done that for.

And so then you start to go back and you look at that Lincoln Douglas debate. You look at the narrative index and lo and behold, the narrative index for Lincoln is double what it was for Douglas. And there it is right there. And that is clear as day that those patterns have been sitting there for 160 years as all these historians have, you know, just fallen over Lincoln and all of his beauty and majesty and, and called him a great orator.

Yes, he’s a great orator, but there’s more than just being a great orator. It’s this ability to structure narrative. To tell things that have a cohesion to them direction and are constantly turning, constantly hitting this moment of contradiction. That’s what activates people’s brains. Then you go back and look at Trump and that narrative index.

Here’s the reference point that we’ve got in the, the first chapter there, the reference ranges. If the narrative index. Is less than 10. That’s really bad. You know, that’s, you’re getting down towards telephone, books and equipment, main maintenance manuals and really, really boring. And there are lots of speeches that people give

Park: that are, and to be clear, that means you’re just, and, and, and that’s it.

Anding your audience to boredom.

Randy: Yeah. Well, and, and with the narrative audit, uh, index it, it’s more saying that you’re just not hitting on any butts. There’s no butts in there. Yeah. You’re not giving any, there’s no

Park: conflict, no contradiction,

Randy: no nothing, no change of direction. And of course, people say, what if you’re using synonyms like however, yet despite people just don’t, you know, it’s butts really the major word that’s used for,

Park: it’s bringing a knife to a gunfight.

Just, just pull the gun out.

Randy: That’s, that’s it. Butt is the butt is the, the gun. Exactly. Or we call it the butt bomb there because it’s so important. So under 10 is really bad. Most politicians, probably 80 to 90% of politicians are in the teens. That’s just really the average sort of of speech that has got that much, uh, narrative strength to it.

And that’s the other thing I talk about, narrative strength is the more you’re using this word, but the tighter the it’s getting, the more you’re pulling people in. Then a lot of the great presidents and speakers, some of them end up getting up to 20 in the low twenties. So a bunch of Lincoln speeches. Um, um, most of his speeches, the majority of his speeches are in the twenties actually, so he was really good.

Kennedy and, and Obama and Clinton, they’re, they’re not that great. They’re, they’re upper teens, something like that. They weren’t punching like that. Then you get up to Lincoln’s probably about the best average I’ve seen of all the ones who’ve done, and a few that are in kind of the, the mid twenties. And then all of a sudden you look at some of Trump’s speeches and especially his debate performance, and he shoots up in the thirties, and there’s no other politician that I’ve found in all these hundreds of speeches.

Probably thousands at this point. Looking at these two metrics, none of ’em shoot up in the thirties. None. None, none. None, none, none. You know, maybe one or two. One has one speech that in the thirties in the book, I have one table that’s 10 of his speeches. They’re in the thirties, and then you look a little more closely and what you see is that that mostly happens when he’s speaking off the cuff off the top of his head.

As soon as he got the, the nominee nomination in 2016, he switched to using a teleprompter and speech writers and Steven Miller in particular, I think, and they came in and they didn’t have the depth of narrative intuition or nor the, the craziness to do the stuff that he does. But you see some of these speeches that he gives out in the small towns that he loves to do to go see the base.

And those are the ones that shoot up in the thirties. And I mean, one of the iconic moments was the Al Smith dinner, that it was a traditional thing that had a kind of roast element to it. And in 2016, and Hillary Clinton was there for it. He just turned into an animal, and that one, I think sws a 37 or a 39 and is just all barbs and all these, I mean, really vicious things that he was saying with her sitting right there.

So when he gets going like that, he shoots way the hell up there, and there is a substance to that. When you’ve got that much contradiction going on, you’re just jabbing and jabbing and jabbing, and that excites the audience. And guess what, you know the January? Yeah. Uh, the January 6th speech. Yeah. Uh, in front of the capitol was um, I think that’s a 2026.

I think it’s upper twenties. And yeah, same thing. You know, he was out there jabbing and jabbing, so he knows how to do that. And I think he had that honed in the media world. And this is, I think the larger lesson for today for the Democratic Party is that we are a media driven society. And there were books, Neil Postman’s book Amusing Ourselves to Death long ago that the subtext kind of warned you better watch out if a candidate ever emerges out of Hollywood that is really entertaining and is really aggressive because that candidate probably is gonna understand media and they’re gonna have this natural.

Advantage and that’s what he’s had. Yeah. Uh, and so, you know, again, I’m not saying anything about who’s the heroes, who the villains. That’s the first thing I say at the beginning of the book. Um, this is about looking analytically at how this guy has succeeded, communicating effectively. And one of the things I addressed early on also is that, um, two or three of my friends enslaved just said, he’s not a good communicator.

How dare you compliment him? It’s not me complimenting him. I got a whole stack of quotes in there from everybody, from Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, to Nancy Pelosi to on and on and out. They all eventually had to concede. This guy really does understand today’s communication environment.

Park: Well, let’s go back at the beginning of this and see, and using my pseudoscience talking to you, the evolutionary biologist, and by,

Randy: by the way, hang on one second.

You know, you know what’s really cool is, is coupling this with. That episode we did of this podcast the morning after the election that Trump

Park: Oh yeah. The first election,

Randy: yeah. Yeah. If anybody’s really interested in this topic, you really ought to go back and listen to that episode. That was the morning I was in DC and you called me up and said, you’ve been warning for a year.

This guy’s probably gonna win this election, and spur of the moment for my hotel room, we did the whole. Episode there and sure enough, and it’s kind of cool, here we are 10 years later. Yeah. Doing this,

Park: going through it again. But going back to that idea of evolution and selection that. I believe, and from learning from you and lots of others that, you know, our, our limbic brain is about survival, right?

I mean, that’s the bottom line is how do I keep this body alive and this person procreating to keep the species going. So if we are communicating and we are boring our audiences to death with, and, and, and, and, and you are not triggering. That limbic brain to pay attention. That’s, but as soon as you insert the butt, that’s a, a plot twist, leading to confrontation, conflict, a problem, whatever.

And that brain wakes up and says, Jesus, I better pay attention to here what I need to do in case this ever happens to me to keep this body alive. And so if we are just being bummed. Bared by content as we are today and not paying attention to a primal narrative framework like the ABT, then we are completely missing our audiences.

And look at how Trump’s doing it. It’s, it, it’s a, it’s a beautiful example of the ABT in action and playing to that brain.

Randy: That’s pretty true. Yeah. I mean, there’s a lot of wreckage across the landscape and at this point, sadly, these two parties are the ABT party against the day.

Democrats have repeatedly run these.

And, candidates who just can’t tell a story to save their soul. It’s very unfortunate. There’s this quote that I use all the time. It’s in one of the, the narrative books from Obama at the beginning of his second term where he was asked, what’s the one, you know, mistake you made in your first term, or the most important one?

And he said, you know, I, my first term, I thought it was crucial to get all the policies straight, and that, that certainly is important. But the job of the American president is to tell a story to the American people. And that’s what it is. And a story involves this basic structure of agreement, contradiction, and consequence.

Park: Yeah. Yeah. So you have a chapter or two in your book or a page that you wanted to share it with the audience. Is this a good

Randy: time to do

Park: that? Oh, sure.

Randy: Let, yeah, let’s, let’s see. I, I just think this is, you know, semi cool, but it, it kind of, here’s what I’ve written. Um, think of a dinosaur bone that you’re holding in your hands.

It was part of something lived long ago. It died, it was buried, and then it was rediscovered. It was dug up, and now it has a new life of sorts in today’s world, the ancient Greeks 2000 years ago knew there was a structure to stories. Aristotle talked about the structure of their plays and the poetics. He realized a good play or story has three fundamental parts of beginning, middle, and end.

This was the start of tripartite three-part ABT thinking. The great philosophers of the 16 hundreds and 17 hundreds also recognized this three-part structure and gave it their own label of thesis, antithesis, synthesis, and then it mostly got lost in the 20th century amid all the increasingly complicated thoughts and models and theories and theorems and ideas of dissertations and books and symposium, and, and, and, and, and it got lost.

Until 1986 and from there I pick up with what happened in 1986, which is great. Screenwriting instructor, Frank Danielle, who was at University of Southern California, he gave a speech that a, a colleague friend of mine, Marty Kaplan at USC. Discovered the transcript of it in 1986, and in that speech, Frank Danielle lays out the ABT dynamic very simply.

He says in two paragraphs, he says, whenever we write a first draft, and he was talking about screenplay, but it’s for anything. It’s for an essay or whatever you’re doing. I. We always began with the dreaded and then, and then, and then structure. That’s what you do. You know, you tell the story of your trip to Europe last summer, and the first version you’ll think of is then we went here, and then we went there, and then we went here.

It’s in the editing and the revisions that you begin to replace those and thens. With buts and therefores, and that’s the makings of narrative dynamics. The buts and therefores begin to turn the buts in particular, turn the direction and give it texture and give it something that can engage an audience instead of numbing them with the end, end, end dynamic.

That was as far as we can tell, the very beginning, 1986 of Frank Daniel laying that out. I took his course in 1995, the year before he passed away. Uh, it was tremendous course, but he never. Made one mention of those three words. And it’s funny ’cause some of my friends that were also in that class, I’ve asked them, yeah, I don’t remember him talking about the three words.

I don’t know why he didn’t use that for teaching. But where they resurfaced in a big way was in 2011 when the South Park guys talked about, I. Using what they turned into by then, what they call a rule of replacing, where they said they’d go into a script and every time they see the word and they try and replace it with a butter.

Therefore, that’s exactly what Frank Daniela talked about in 1986. That’s where I heard about that dynamic and began talking to people and eventually took that and shaped it into this single template of the ABT. Circling back to that graphic that you said with those six different models, it, it, it, I, I thought that was kind of nice seeing that because it’s been a pretty long journey.

15 years of pounding away, getting this thing out there, and it’s getting there now. And we’re working with so many big organizations and everybody from the World Bank to FAA right now in particular, um, helping them. And it’s a course now at Emory University Medical School. This fall will be the fourth year in a row teaching it to medical students.

And they love it. They’re, they’re very proud of it. Um, it’s just very powerful. The ABT is given a few more years. Tons and tons of people will be using it because it’s so simple. It’s the tool that’s needed for a world of too much information, which is what we’ve got now. And all of these groups we go in with, that’s what we do.

And just one little thing to relate, just last week, I mean week after week now, it’s so much fun. It’s been a long journey, but now is the big payoff Last week. One of the top scientists at, at one of the groups that we work with, I won’t mention which group, but contacted me and he is applying for. A job with a big ai, one of the big AI firms and, you know, super competitive thing, and had to write a 400 word essay in the morning.

He sent me his draft of the 400 word essay, and it was a mess. You know, it was all and, and, and, and it had a bunch of bits and pieces, but it just did not have clear narrative structure. So what I did was sit down that morning. Do our color coding that we do in the course. You know the three elements we color code them.

So the, the setup material, the and material, we color code it blue, the problem, the contradiction. We, we color code that red and then the consequence or the therefore element, we color code that green. And as you read through his 400 words, every single sentence is, what you do is you color code each one and you just look at, read the sentence.

Is that a statement of setup stuff or is that a statement of, of problems, things to be worked on. Is that actually the actions that are going on. And once I got through color coding, all the different sentences, all the way through the 400 words, you could see, you know, it just looked like a mosaic. But then you start lumping together some of the blue ones together and the the red ones together, and you try and shrink the red ones down into a single problem and get all the green ones, all the yada, yada.

And out of that, I gave him a bunch of notes by, right before lunchtime he went to work. And then the afternoon sent me a couple drafts and. At the, by the late afternoon, I read the draft that he had to two of the people in my group and they were like, God, that’s a great essay. It all came together thanks to the ABT.

It got that structure and he was thrilled by the end of the day. And to just get experience like that, the structure stuff is so important, but you’ve got to have this set of kind of guiding rules of how these things come together because there is a logical. Way to put this together and that’s where we talk about the ABT as being like puzzle solving you.

You sit there and you stare at the material and you rearrange things. Wait, now this thing down here, it’s in the there for right now. Look, well look what happens if you move it up here to the opening, the, the an oh my goodness. It’s all completely different. That’s what the whole process is.

Park: Our listeners here mostly are not scientists and academics.

They’re business people and they’re trying to communicate and connect. And the reason why you should read, I believe, Randy’s 12th book on storytelling because it spurred That’s right. It’s short. It’s a really fascinating look at the history of narrative and how. It is, you know, we are selecting to that set up problem resolution dynamic like never before, but I’ve taught the ABT to the United States Air Force Leadership, Dell Computer, Intel, Walmart, Canada, Mayo Clinic, you name it from the business side, and why it’s important for you as a business leader is if you truly.

Want to connect with your people and move them to action, then you have to look at your prose. You have to look at your presentations, and chances are you are and and anding your audiences to death with complete boredom. And, but therefore Randy has given us two absolute great metrics to do it. The and frequency, which he really details in the book and shows you how to do it.

Take all of your, and divide it by your words.

Randy: Lemme toss in one thing there with the and frequency. Mm-hmm. That blows my mind, you know, to use a cliche or whatever. There is this perfect value for that. There’s the optimal value, 2.5%, and when you analyze the articles in the New Yorker and the New York Times and the Atlantic, as we’ve done.

They all end up right around two and a half percent of all the words of the document are the word and why this is some linguistics. People need to go to work and figure out mechanically why does this happen? ’cause I guarantee you all those editors in New York are probably not a one of ’em, knows that this is what happens.

But when material goes through a really well-structured brain, it comes out with 2.5%. Of all the words being the word and, and that means all you have to do with a word processor is look at your, just search your thing, the total number of ands, and divide that by the total number of words. And if it’s near 2.5%, you’re doing pretty good.

But if it’s over three, you’re starting to get boring. If it’s over four. You’re boring people and if you go anywhere near five, you’re in the government report range that are literally unreadable. You can’t get through an end. An end document when it gets up over 4% is

Park: really, and what I learned too, when you’re doing that, you’re searching your document.

You have to have a space before the A. That’s right. And a space after the D. That’s right. Because you’re gonna end up with ands inside of words like land and that kind of thing. I learned that the hard way. So you, you just take those and divide it by the total, and then you take your butts. Divide ’em by the number of ands and you times it by a hundred to round it up, and that gives you your narrative index.

And what are there, what’s the ideal score in the narrative index?

Randy: Two point a half percent. Oh. Oh, no. So that’s nos. The, and that’s and frequency. Yeah. Okay. No, the, um, the narrative index, uh, doesn’t have that thing. That’s why it’s so fascinating with the in frequencies that there’s a single number, that two point half percent, the narrative index is the one that incorporates the word, but in there.

It’s just basically the more butts that you’ve got going in there, the better overall. And then to within reason. I don’t, I don’t know. You know, the ones that have got enormous scores up in the thirties, man, they’re all really powerful. I’ve, I’ve yet to see something that’s a train wreck that has, when you see a really bad speech, it almost can’t have a really high but to end ratio.

It, it all, the bad speeches and all the boring stuff are all. Way down there, they’re just swamped with ants. Uh, ’cause nobody’s putting together clear, coherent ideas.

Park: But if your but to end ratio is not in the teens, you are really boring. If you’re in the teens, you’re kind of interesting. If you’re in the twenties, people are going, oh yeah, I gotta really pay attention.

If you’re in the thirties, you can run for president of the United States

Randy: Maybe. And what’s so insane, and well, a side note on that, which is all the great standup comics. There’s a website called Scraps from the Loft from the New Yorker, and they’ve got hundreds of, uh, transcripts of standup comics, famous performances, and we’ve analyzed a ton of those and they turn out to be the best communicators in our entire society.

They have to know this ABT stuff to stay alive. They cannot afford to bore or confuse people, and they score routinely in the thirties, standup comics. And that’s what’s fascinating. So you don’t find any politicians shooting up there other than Trump. But the best standup comics are, are in there over and over again.

And then they’re just all these old curiosities. Like, here’s one of the the things that drives me crazy. George W. Bush gave seven State of the Union addresses all seven of them. The narrative index is five or less, and as we just said, under 10 is already getting bad. All five, all seven of his State of the Union dresses are seven or less.

And how do you do that year after year with just no buts, nothing, no contradict, no storytelling, nothing, just blah, blah, blah, blah. That’s what’s there. You know, I defy somebody to go study his seven State of the Union addresses, or nothing memorable for me, any of that junk. Um, and then one tiny little quirk with that.

I just noticed yesterday I was putting the finished touches on the book. He used the word yet a lot, almost nobody uses yet. And he’s the only person I’ve seen in some of those speeches. He had almost as many yets as buts and so I don’t know he was fond of yet. That’s, that’s really a weird thing, but you know, that’s what you would expect.

And then the last thing to say in the, the last of the three appendices in the book that’s really fun, oh God, we, we can go on for an hour about this, is you can then use these two metrics to do forensics basically. Because you can make predictions of what something should be. And so here’s the little vignette that I offered at the beginning of that thing is imagine you found this manifesto from a serial killer and you know it’s 34,000 words, and you dive in there and you do the two metrics on them, and imagine that the scores come out and they are.

You know, a, a 35 for the narrative index and a 2.6 for the, the, and frequency that are like super duper high scores that tell you it’s really, really well written. And then you start looking at suspects and you look at their, the papers that they write or something like that, you know, if they’re somebody who’s a writer, who knows what, and if, you know, if that person writes and, and, and stuff, and you’ve got this manifesto, that’s way the hell up there.

There is no way that that guy is likely to this. It’s not definitive proof, but it’s just like another piece of forensic evidence that you put into the body of, of evidence that you present eventually. And then when you actually go and look at the Unabomber manifesto, that was his scores, A 35 for the narrative index.

Way the hell up there, right next to all of Michael Creighton’s speeches that ever, ever gave. And then the other day I, I asked ChatGPT, you know, is the Uni bombers manifesto re. Regard is well written and yes, absolutely. You know, it’s, it’s gotten a whole life of its own online because it is so well written.

And that’s the thing, you know, these things will not persist if they’re unreadable.

Park: Well, it gives a whole new meaning to butt bomb, doesn’t it? Yeah, it really does. He was the ultimate butt bomber. He was the butt bomber. And with that, your book is coming out like right now. People can go to Amazon and pick that up and tell us real quick about your website where people can go and learn more.

About the ABT framework.

Randy: You know, we’ve moved everything to substack now, and so. I’m on there, uh, on Substack and I think that I’m the world’s worst promoter for my own stuff. So just search Randy Olsen’s Substack and it’ll take you there. I think should have had Matthew David join us here. He is the guy in charge of all that stuff, and he could tell you exactly where to find it, but I’m sure that’ll take you right to it.

Randy Olson.

Park: We’ll find the link and I’ll get it. I’ll put it into the show notes. Yeah, and, and

Randy: our website is ABT narrative.com. That’s where all the basics are, but it’s, it’s all moving to Substack now. Yeah, that’s

Park: our home. Awesome.

Randy: Yeah, and put that on your, your site, whatever the link is. PA Park. Thank you so much for all that you’ve done in ABT land, not just having me on your show, but you know, you have spoken, we’ve done 42 rounds of the ABT course, um, that we started right at the beginning of the pandemic.

- You’ve spoken more than in 30 of those rounds, so you’ve been one of the stalwarts there. As we’ve continued to build this whole body of knowledge around the ABT and now it’s, it’s so fun to be able to share it with all these groups and to be able to. Use it to tighten up and improve communications all over the place and in particular stuff we’re doing right now with both the World Bank and FAA where they really need help in quote, telling both of those groups contacted me the last two or three months saying, given current events we really need help in telling our story.

And so we’re up to our neck and use the ABT with that.

Park: Well, you’re doing important work out there. I love this new book. I love the cover of it, and uh, I really recommend all of you to dive into Lincoln, but Trump, it will completely change the way you communicate out there. Thank you, my friend, Randy, for being here.

It’s always a pleasure.

Randy: Always a good time talking with you, the master of the DNA of story. All

Park: Right, man. I’m gonna catch up with you soon.

Randy: Cool.

Park: Thanks for listening and sharing this show with anyone you know who would be interested in the similarities and the contradictions between Lincoln. And Trump and how to use the narrative index and the and frequency to make their and yours communication stronger, more clear, more concise, and ultimately more compelling to move your audiences to action.

Hey, to help you really build the foundation around your brand story, I hope you have registered for our Story Cycle Genie Launch. It will enable you to create and craft a lucrative. Brand narrative strategy in minutes, not months, at a fraction of the cost of the old traditional way of branding, plus the story cycle.

Genie will create every conceivable piece of content you can imagine, all based on your. Brand narrative. And again, it does it on in minutes, not months, with pennies on the dollar versus what you normally pay for that stuff. So check it out, business of story.com/story cycle dash genie. Register now for the launch and save 75% off the launch of the Genie.

Join me next week when. The amazing Rand Fishkin will be here. Rand is the CEO of Spark Toro, the makers of fine audience research software. He’s also an indie game developer at Snack Bar Studio. So it’s gonna be an engaging conversation because we’re gonna dive deep into truly understanding your audiences and how to connect with them on a very.

Deep, visceral level knowledge you can use as you run your brand story through. You guessed it. This story Cycle Genie. Check it out, business of story.com/story cycle dash genie. Thanks again for listening. And remember, as you grow as a more confident, compelling, and respected communicator using storytelling, that the most potent story you’ll ever tell is the story you tell yourself.

So may. That one. Epic. I appreciate you being here. Thanks for listening.

Listen To More Episodes

Listen To More Episodes