Once I learned about the Hero’s Journey from Joseph Campbell’s work, it started appearing everywhere. This universal pattern to story permeates all of our lives. It’s not only in the stories we love, the movies we gush over, and the music we call our own, but it’s also found in our everyday activities. That’s why stories, and the Hero’s Journey they are structured upon, are mirrors of life’s struggles and victories.

Once I learned about the Hero’s Journey from Joseph Campbell’s work, it started appearing everywhere. This universal pattern to story permeates all of our lives. It’s not only in the stories we love, the movies we gush over, and the music we call our own, but it’s also found in our everyday activities. That’s why stories, and the Hero’s Journey they are structured upon, are mirrors of life’s struggles and victories.

Campbell’s work inspired me to create the Story Cycle, a 10-step process that helps guide our agency’s approach to everything from high-level brand strategy to the story structure of tactical executions, like TV and radio spots, print ads, website user experience, etc.

I have written a communications course based on our Story Cycle and am honored to be teaching it in the new Executive Master’s for Sustainability Leadership program at Arizona State University. My goal is to turn sustainability executives into Chief Storytelling Officers so they can own the boardroom, break room, chat room, and living room to help advance their social initiatives further, faster through the power of story.

The Story Cycle is not a formula. It’s a form that allows you to capture the necessary information you need to get the mind, which is hardwired for narrative, to embrace your content. Although I ask our students to capture their content in this order, I encourage them to move the chapters around and add their own creative nuance to make the stories uniquely their own.

The 10 Steps of the Story Cycle

- Backstory = What is the setting for your story?

- Hero = Who is the story about?

- Stakes = What do they want?

- Disruption = What are the changes in life that your hero must address?

- Antagonists = Who and what must they overcome?

- Mentor = Who helps them?

- Journey = How does the hero’s quest unfold?

- Victory = What does success look like?

- Moral = What is the truth your story reveals?

- Ritual = How does your hero use the enlightenment from his journey to become a better person?

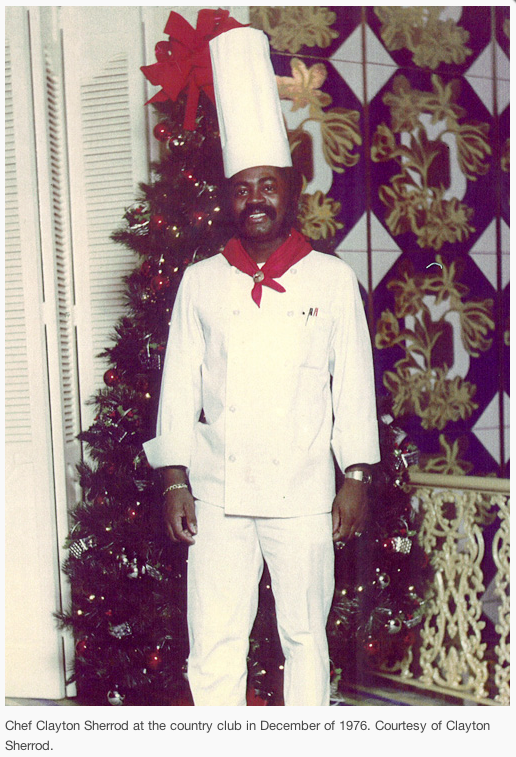

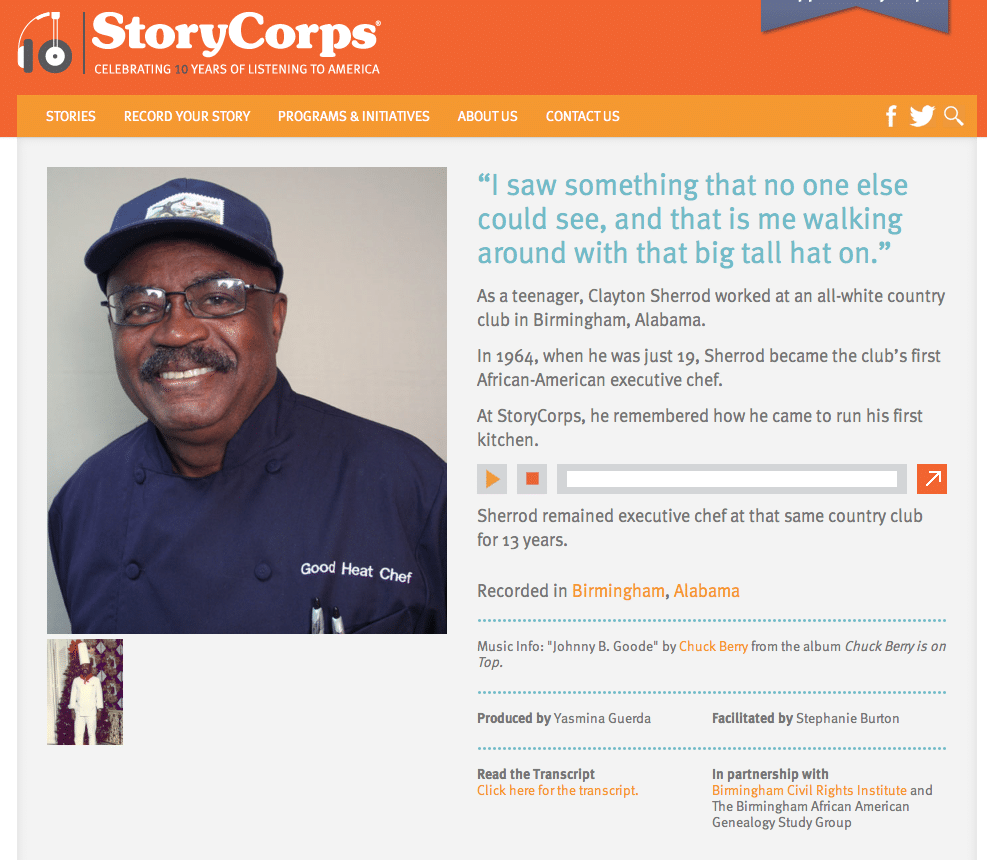

Here is an example of what I’m talking about. Listen to Clayton’s amazing short story – not written by Hollywood, but crafted by life – and see if you can identify each chapter of the Story Cycle. Then test your knowledge against the anatomy of his story that I have outlined below.

Here is the anatomy of Clayton’s story based on the Story Cycle

Inciting Incident

“My father had a heart attack.”

Backstory

“I was like 13 years old and my mother said, ‘You can’t go back to school, you’re going to have to find a job.’ So I went to the country club.”

Hero

“And I always wanted to go up to the kitchen and wash dishes because it was really fascinating to see those guys cooking.”

Stakes

“So I made up my mind that I was going to be a chef. All my friends told me I was crazy but I saw something that no one else could see, and that is me walking around with that big tall hat on. So I counted how many positions it was from washing dishes to the executive chef. And we had like a three room house. So what I did, I had my chart pinned to the wall in our little outdoor bathroom there and I would mark every time I got a promotion, And then I would turn the light off and I would dance. And I would sing “Johnny B. Goode” and I changed it to “Clayton B. Goode, you’re so good.”

Antagonist

“You know I didn’t mind all the hard work–actually I loved it. I worked the whole weekend without going home. And I worked myself up to sous-chef, and there was this guy named Frank Cahey who was executive chef. He told me one day, he said, “I know what you’re trying to do. You think you’re going to be the chef here.” He said, ‘But I’m going to be here for life.’ He said ‘You might as well either keep working under me or go somewhere else.'”

Journey

“So what I did, I was sneaky. You know in the back of trade magazines there are articles in there looking for chefs all over the country. I wrote one of the best looking resumes and signed Frank Cahey’s name on it, and sent it to all of these head hunters all over the country. And he actually thought he was famous, he said everybody knows about him. But he didn’t know it was me that did it.

And the general manager got tired of it. He’s like, ‘Frank, every time you come to me for raises, and people want you here, people want you there.’ He said, “Right now, at this very moment, I consider you dead.'”

Mentor

“Frank, he turned white as a sheet and he said, ‘Well what are you going to do?’ He said, ‘Well Clayton, can you take care of it until we find another chef?’ I said ‘I’ll be more than happy to.'”

Ritual

“That’s all I needed. I never even looked back.”

Moral

I believe the moral of this story – the truth that teaches – is found in something Chekov once wrote: “Man is what he believes.” Or another moral might be a truism from Aesop: “A fine appearance is a poor substitute for inward worth.” Or a moral I just drummed up: “Vanity is no match for industry.”

We love stories because the good ones teach us about life. Stories connect the shared values of the storyteller and the audience. If you’re stories aren’t sharing a truism, then you need a better story.

at 5:59 pm

What a fabulous story and useful illustration of your Hero’s Journey work. thx